In a previous article, This is not a manifesto, I expressed the values I hold as a software development team member. Today, I’m going to talk about the first of these values.

Before I do, I’d like to say what I mean by “software development team”. I mean a cross-discipline team with the combined skills to deliver a software product – product owner, user experience, business analysts, programmers, testers, dev-ops, etc.

A common problem

Many teams I encounter will, at least in the beginning, have team-members who specialise in a single role. Each team-member will rarely, if ever, step outside their job description [1]. This can cause a problem.

Many teams find themselves in a situation where some team members have little to do on the current stories. At this point, the team has some choices, they can focus the under-utilised people on:

- Future user-stories, working on tasks most relevant to their job title

- Another team, working on tasks most relevant to their job title (e.g. ‘matrix management’)

- Current stories, taking on tasks that will take the story to completion sooner, even if it’s more relevant to someone else’s job title

- Things that will make the more utilised people get through their work faster, today and in the future.

More often than not, I find teams taking option 1. I think that people choose this option because it feels like it should increase the throughput of the team – i.e. the amount of new features they can add to the product. In fact, it has the opposite effect.

Little’s law

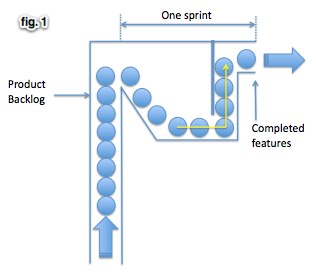

Let’s consider a team that is working in time-boxes or ‘sprints’ (à la Scrum) and measures it’s throughput with ‘velocity’ (story-points per-sprint). Points are accrued as each user-story is completed – i.e. coded, tested and product-owner validated.

In this particular team, it is able to complete an average of 10 points per sprint. Let’s say this is due to a bottleneck in the process. This bottleneck might limit the amount of testing that can be completed during the sprint. This is illustrated in fig.1 where each ball is a story point.

Little’s law [2] tells us that the amount of time it takes to complete an item of work (cycle-time) is:

Work in Progress (WIP)

Throughput

Which we can read as:

story points in progress

velocity

In this simplified example, WIP is 10 points and throughput is 10 points per sprint. The average cycle time of a story is therefore 10/10 = 1 sprint. Notice, however, there’s all that spare capacity.

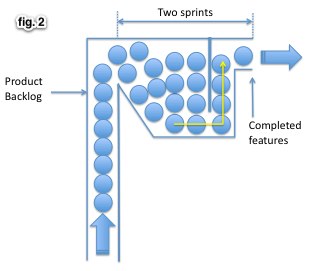

Let’s say this spare capacity is developers. So, the team starts taking on more user-stories from the backlog – increasing the number of story points in progress to 20 points (fig.2).

Because the bottleneck remains, velocity remains the same – 10 points per sprint. The amount of flexibility that the team has, however, is now reduced because the average time required to get a story to completion has increased from 1 sprint to 20/10 = 2 sprints [3].

Often this will take the form of testers working a sprint behind the developers. Worse still, over 10 sprints, the team still only completes 100 story points (as they would have before) but is left with a lot of unfinished work. This ‘inventory’ of unfinished work carries overheads which can, ultimately, reduce the velocity of the team.

The impact of filling capacity in this way has yet another effect.

Latency effect

As the developers get through more stories, a queue of stories that are “ready for testing” will build up. Testers working through these will, at least, have questions for the developer(s) or even find some defects. The developer, having moved on from that story, is now deep into the code and context of another story. When the tester has questions, or finds defects, relating to a story that the developer had worked on, say a week ago, then the developer has to reload their understanding of this old code and context in order to answer any questions or fix any defects. This context-switching carries significant overheads [4].

The end result is that the effort required to complete a story increases due to the repeated context switching, therefore reducing velocity.

So, not only does filling the capacity with more work fail to increase throughput, it adds costly context-switching overheads – ultimately slowing everything down.

This phenomenon is not unique to teams using fixed-length time-boxes, such as sprints. Strictly following Kanban avoids this problem, but what I’ve seen is some teams creating a ‘ready for testing’ queue – so that developers can start work on the next story. This has the same latency effect and turns a process designed for continuous flow into a batch and queue process. But, I digress.

What to do with the spare capacity?

The simple answer is to look at the whole approach and determine what is slowing things down. In the example above, I’d be wondering what’s slowing the testing down. Many of the things that hinder testing can be addressed by changing how we do things ‘upstream’.

Are lots of defects being found, causing the testers to spend more time investigating and reproducing them? Can we get the testers involved earlier? Can any predictable tests be defined up front so that developers can make sure the code passes them before it even gets to the testers (e.g. Behaviour Driven Development)?

Are the testers manually regression testing every sprint? Could the developers help by automating more of that? Are the testers having to perform repetitive tasks to get to the part of the user-journey they’re actually testing? Can that be automated by the developers?

Is there anything else that is impacting them? Test data set-up and maintenance, product owner availability to answer questions? Anything else?

Addressing any of these issues is likely to speed up the testing process and increase throughput of the entire team as a result. One solution is to put these types of tasks onto the product backlog. This is fine but if we assign point values to them it can give a skewed view of velocity. Or rather, velocity is no longer a measure of throughput. You won’t be able to see if these types of tasks are actually improving things unless you are also measuring what proportion of the points are delivering new product capabilities.

The only good reason I can think of for story-pointing these throughput-enhancing tasks is if your focus is utilisation – i.e. maximising the number of story-points in progress. Personally, I care more about measuring and improving throughput. By doing so, we get the right utilisation for free and a faster, more capable team.

Up next: Valuing Effectiveness over Efficiency.

Footnotes:

[1] “Lessons Learned in Close Quarters Battle” Illustrates how stepping outside our job descriptions can move the team through each story more quickly by using special-forces room-clearing as an analogy.

[2] Little’s law (PDF) – the section “Evolution of Little’s Law in Operations Management” that references Hopp and Spearman’s observation about throughput (TH), work-in-progress (WIP) and cycle-time (CT) – i.e. TH=CT/WIP. And therefore we can say CT = WIP/TH.

[3] Little’s law also illustrates that if we reduce the work in progress to one quarter, then the cycle time for each story reduces to one quarter of a sprint. We’ll still get through 10 points per sprint, but stories will be completed more as a continuous stream throughout the sprint rather than all at the end.

[4] “The Multi-Tasking Myth” by Jeff Atwood, talks about multi-tasking across projects and pulls together several resources to illustrate the impact of multitasking at various levels. This applies when multi-tasking across stories.

Acknowledgements:

I’d like to say a special thank you to my fellow RiverGliders – Andy Palmer and James Martin – for the feedback that helped me refine this article.