There’s something wrong with many behaviour specs (or acceptance tests). It’s been this way for some time. I’ve written about this once or twice before, referencing this post by Kevin Lawrence from 2007.

So, first things first, I want to take this opportunity to update the terminology I use…

Goals -> Tasks -> Actions

A useful technique used in User-Centred Design (UCD) and Human Computer Interface (HCI) design is Task Analysis. There are three layers of detail often talked about in Task Analysis:

Goal: What we’re trying to achieve which has one or more…

Tasks: The high-level work-item that we complete to fulfil the goal, each having one or more…

Actions: The specific steps or interactions we execute to complete the task.

Previously, the terms used by Kevin, myself (and several others) were Goal->Activities->Tasks. From now on, I’m going to use the UCD/HCI/Task Analysis terms Goal->Task->Action. It’s exactly the same model – just with different labels at the three layers of detail.

What’s wrong with your average behaviour spec?

Let’s look at a common example… The calculator. For convenience, I’m going to borrow this one from the cucumber website[1].

Scenario: Add two numbers

Given I have entered 10 into the calculator

And I have entered 5 into the calculator

When I press add

Then the result should be 15 on the screen

[1]note: I’m using this example for convenience and simplicity. The value of the example on the cucumber website is to demonstrate how easy cucumber is to use and not necessarily as an exemplar feature spec

What would you say the scenario’s name and steps are representing? Goals and Tasks or Tasks and Actions?

I’d argue that adding two numbers is a task and the steps shown above are actions.

Instead, I try to write the spec (or test) with a scenario-specific goal and the steps as tasks.

Scenario: sum of two numbers

When I add 10 and 5

Then I should see the answer 15

I.e.:

Scenario: <A scenario specific goal>

Given <Something that needs to have happened or be true>

When <Some task I must do>

Then <Some way I know I've achieved my goal>

Another Typical Example

Let’s apply this to another typical example that might be closer to what some people are used to seeing:

Scenario: Search for the cucumber homepage

Given I am at http://google.com

When I enter "cucumber" into the search field

and click "Search"

Then the top result should say "Cucumber - Making BDD fun"

Again this is talking in terms of actions. As soon as I’m talking in terms of click, enter, type or other user-action, I know I’m going into too much detail. Instead, I write this:

Scenario: Find the Cucumber home page

When I search for "Cucumber"

Then the top result should say "Cucumber - Making BDD fun"

Why does it matter?

In the calculator example, the outcome the business is interested in for the first scenario is that we get the correct sum of two numbers. The steps in the scenario should help us arrive at a shared understanding of what ‘correct’ means. How we solve the problem of getting the numbers into the calculator and choosing the operator is a separate issue. That’s detail we can defer. It may be better to explore the specifics of the workflow using, sketches, conversation, wire-frames or by seeing and using our new calculator.

So, expressing our scenarios in terms of goals and tasks helps the delivery team and the business arrive at a shared understanding of the problem we’re trying to solve in that scenario.

Expressing the scenario in terms of the clicks, presses and even fields we’re typing into is focusing on a solution, not the problem we’re trying to solve.

But there’s another benefit to doing it this way…

A Practical Concern – Maintainability

The first calculator example follows reverse-polish notation for the sequence of actions:

- enter the first number

- enter the second number

- press add

If we put that detail in the scenarios, that workflow will be repeated everywhere – for addition, subtraction, division, multiplication… and anywhere any calculation is described.

What happens if the workflow for this calculator (such as the UI or API) changes from a reverse-polish notation to a more conventional workflow for a calculator? Like this:

- enter the first number

- press add

- enter the second number

- press equals

The correct answer hasn’t changed – i.e. the ‘business rule’ is the same – it’s just the sequence of actions has changed.

Now we have to go through all the feature files and update all the scenarios. In the case of our calculator that may only be a few files covering add, subtract, divide, multiply. For something larger and more complex this could be a lot of work.

Instead, putting this in the code of the step-definition means that this:

When ^I (add|subtract|divide|multiply) (.*) (?:and|from|by)? (.*) do |operator, first_number, second_number|

@calc = @calc ||= Calculator.new

@calc.enter first_number

@calc.enter second_number

@calc.send operator.to_sym

end

Would have to change to this:

When ^I (add|subtract|divide|multiply) (.*) (?:and|from|by)? (.*) do |operator, first_number, second_number|

@calc = @calc ||= Calculator.new

@calc.enter first_number

@calc.send operator.to_sym #moved up from the bottom

@calc.enter second_number

@calc.calculate #new action for the conventional calculator workflow

end

Nothing else would need to change – other than the product of course. By writing the steps as tasks, all of our feature files would still accurately illustrate the business rule even though the workflow of the interface (gui or api) has changed.

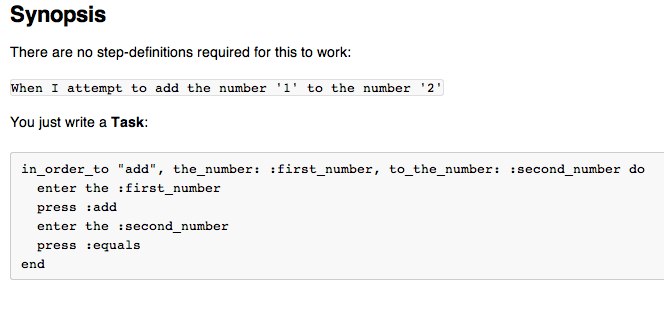

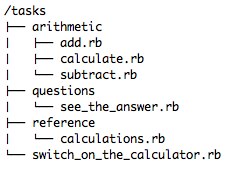

Taking your scenario-steps to task

So, taking this approach helps us to reduce our maintenance overheads. Putting the Actions inside the step definition makes our tests less brittle. When the workflow changes we only need to update our specs in one place – the step-definitions.

Of, perhaps, greater importance – by capturing the user’s scenario-specific goal as the scenario name and the tasks as the steps, the team are working towards a shared understanding of the part of the problem we’re trying to solve not a solution we might be prematurely settling upon. When rolled up with the broader context (expressed in the user-story and its other scenarios) it gives us a focus on solving the wider problem rather than biasing the solution.

Sometimes, at first, it’s hard to see how to express the scenario and is easier when people start by talking of clicks, presses and what they’re entering. And that’s ok. Maybe that’s where the team needs to start the conversation. Just because that’s where you start, ask “why are we doing those actions” a few times, and it doesn’t have to be where you end up.