For many years I’ve been coaching software teams in various things such as Example Driven Methods (xDD), including BDD and TDD; pair-programming; programming; testing; retrospectives; Scrum, kanban and various other ways of getting the most out of a development team. One thing that I notice is that while the teams are being coached, they do amazing things. They are more happy, more productive, fast to improve as if there are no limits to what they can achieve.

Then, at some point they decide that it’s time to go it alone. I always say to my clients to keep at least one day in their budget for me to go away and come back some time later. Usually within a month or two to see how things are going. Inevitably when I return, the team is doing reasonably well, but not as well as if I’d stayed involved, even if I was just popping in once every couple of weeks.

Some say that this is what the Scrum master is there for, however, I’ve noticed that this is something that the Scrum master doesn’t get to do much of as they are are often dealing with external pressures “to get things done”…

On many teams, once I move on, there is a coaching void. Despite my pleas and efforts to encourage them to at least establish a coach from someone in-house, the team is often left to just get on with it.

This isn’t a new idea. For example, Extreme Programming highlights “the coach” as a key role in the team.

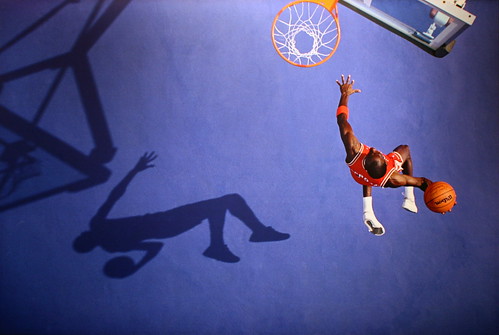

In sports, teams have coaches. Have you ever heard of a professional sports team without a coach? Can you imagine a professional sports team hiring a coach for a while and then saying – “we think we’re ready to compete on our own now so thanks for your help but you’re not needed anymore”. No, I don’t think so. This is unheard of in competitive sports, yet all too common in competitive business.

Even my 12 year old son’s basketball team, the Islington Panthers, has a coach. He trains them 2-3 times per week and he (or an acting coach from the seniors) attends all of their games. In some training sessions he gets a member of the under 21s team to coach the under 13s training session – so there is always a coach even if they’re just borrowed from another of the club’s teams. Without him, do you think any of the club’s teams would make the national play-offs as they regularly do? Very unlikely.

So, competitive sports teams always have a coach. Temporary coaching in a professional sports team is almost unheard of… Sure, they could get by but would they be taken seriously? Would they be competitive? Would they save money by not having a coach or would this be an obvious false economy? What are their chances of generating sponsorship revenue if they are not winning games? What are their chances of winning games without a coach?

The same applies in software teams. For example, I worked with a client recently and helped a team of 6 people double their output in one day. They’d have to hire another 7-10 people in order to achieve that but instead, one good coach was enough.

So, if you have a professional software team without a coach, consider, are you really helping your business save money by going it alone? Or, like the professional sports team, is having a professional development team without a coach another example of a false economy.