This was originally posted on my old blog on 10th April 2010

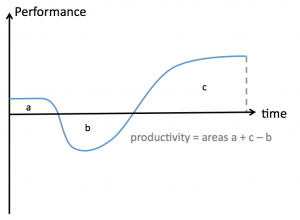

Recently, I wrote about my views on using and estimating with task-cards. I highlighted that tracking progress with burn-up/down charts showing effort completed/remaining is not a true measure of progress, especially if we subscribe to the idea that we measure progress with working-software.

I also highlighted how tasks “horizontally slice” a “vertically sliced” story.

This inspired an article on infoq by Mark Levison. Since its publication, there have been several comments.

There are some specific points I’ll be answering on infoq, but some general points are more easily answered here…

True measures of progress

One of the key points I was trying to make in my first post (linked to above) is that if “working software” is our measure of progress then tracking task completion is not consistent with that.

One of the problems task-hours are trying to solve is to provide a visible indication of progress. It’s also something that many people find easier to understand. The idea of relative-points estimation seems to baffle many people when they first encounter it.

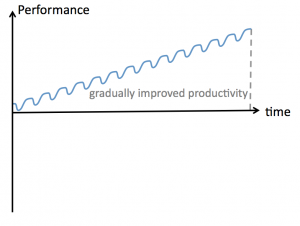

In my original post (linked above) I referenced an approach, blogged about by Jason Gorman, outlining a solution to providing a visible indication of progress that is compatible with the idea of measuring progress with working software. It also works more seamlessly with the solution of measuring throughput trends of the team (e.g. with story points) so that the team can estimate how much can be done in the next iteration.

Value Points & Task Points

Value points were mentioned in the infoq comments. Value points are solving a different problem and don’t help the team estimate what can be done. The value of a story isn’t an indication of its complexity. Value, combined with complexity points, can help determine priorities. Arlo Belshey explains some interesting views on this.

Prioritisation is, in my view, one of the few reasons to place some sort of estimate on value & complexity. Unfortunately, it seems to be often used to establish a contract with the team for when something will be done and apply pressure when the estimates turn out to be inaccurate.

Non-estimating pull systems

My preference is to use such estimates only for prioritisation… after that, things just take as long as they take. There is some benefit in tracking accuracy trends so that we can learn from them, however, spending too much time on these things simply slows down the process of getting things done. Interestingly, I have not yet seen the business be quite so passionate about evaluating whether their value estimates were accurate when the product makes it to the real world. Funny that.

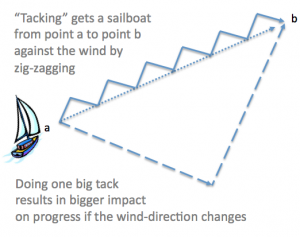

Instead, I prefer to leave estimation behind once we’ve prioritised things and pull stories or customer valued work items through the system without using previous estimates to predict their completion date. With the way that most budgets are determined and allocated, this idea isn’t compatible with the way much of the business world works. For pull systems that eliminate estimation as a means of predicting the future to work (such as Kanban), we need a more adaptive approach to budgetary spend. Business needs to find a way to adapt budget allocation more frequently, perhaps as frequently as monthly, perhaps more frequently still. The business now needs to look at how it can respond to change rather than focus on following a budget-plan.

Business-world: now it’s your turn

Budget holders now need to be more agile. We, those who evolve the implementation of the ideas of the business, have responded to their demands to be able to respond to rapidly changing markets and provide that competitive edge. For the more mature implementation teams, the hindrance now is no longer how we make the products, but the business culture of inflexible and predictive budget allocation.