One of the key characteristics of how we coach our clients’ teams is that we help them start from where they are and introduce small, frequent changes that help them progressively achieve their goals.

Each incremental change is driven by a problem the teams recognise they are facing. We then help to find a small change they are happy to introduce as an experiment. This change must be a solution or a step towards a solution to the identified problem. Sometimes this experiment will be limited to a single iteration. Sometimes it’s limited to a single user-story in a given iteration.

Based on the outcome of the experiment, the team decides what to do next. They may continue the experiment, introduce the change beyond the limitations of the experiment or even abandon that change and try something else.

This has two distinguishing factors.

1. Solving Problems: We focus on solving problems not introducing solutions

2. Continuous Improvement: Delivery continues, becoming increasingly productive

1. Solving Problems: For example, we’ve often been contacted to ‘introduce TDD’ or ‘transition a team to Scrum’. Usually, we find that behind these solutions are problems that our client instinctively understands are there but articulates them as these kinds of solutions. Sometimes they want to reduce the amount of re-work, or get early visibility of achievable scope within a time-constraint. Other-times it’s a solution for solution sake.

By solving the problems the people in the organisation recognise as holding them back, they are bought into each change. Sometimes our job is to help them recognise the problems. Retrospectives are a great way of achieving that.

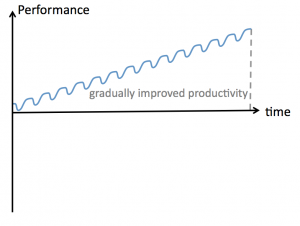

2. Continuous improvement: When helping an organisation to solve the problems they face they expect large and significant change. Instead we help them make a continuous series of small, team-driven changes. This allows them to continue to deliver with the net effect of gradual and continuous improvements in productivity.

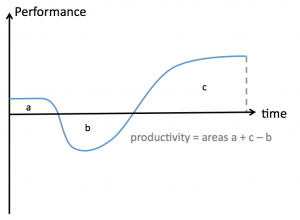

We generally find ourselves taking this approach because for most of our clients, big-bang change is not practical simply due to the impact on productivity. We can understand this using the Satir Change Model (explained very well by Steven Smith).

In this simplified and slightly adapted representation, you can see that with a large change there is a period of net-negative productivity. Once the improvement starts to take hold, performance increases take productivity back into the black.

On rare occasions when an organisation’s software reaches critical mass (it’s more expensive to change than to replace) big-bang changes might be necessary. We’ve worked with a client that had exactly that problem. They took the brave step of ceasing delivery while they redefined how they did things and coached their teams in how to do it. This worked out positively for them. After about 6 months of intensive coaching and 3 months of implementation they delivered a revenue generating system to replace something that had been previously worked on for 18 months and had remained incomplete.

Most organisations would find it difficult to take that step and need to continue to deliver whilst transitioning from how they work today to how they want to work in the future. It is for this reason that we find ourselves employing small incremental changes, eliminating the things that add friction to their process – one problem at a time. Doing this with small experiments helps the organisation limit the risk and achieve continuous delivery and continuous improvement.

A way of understanding how this works is with the same Satir Change Model. If we take the curve shown above illustrating big-bang change, shrink it so that each change represents a much smaller alteration to working practices and then repeat, what we end up with is a much healthier looking series of changes.

Yes, each change can slow productivity temporarily but the impact is dramatically reduced and quickly offset by the improvements gained.

The area under the graph is productivity. If the changes are small enough there is never any period of net-negative output.

Another reason this works well is that it reduces the amount of cultural resistance that you have to deal with. Instead of a lot of resistance from many people for complex reasons, you tend to have only a few people resisting the change. Because the change is driven by a need to solve a recognised problem you have more people in favour of the change. Because change is frequent, people get used to change. In fact, they become experts at it and no longer resist the mere idea of change.

Commercially, it also gives you much more flexibility and allows you to adapt your vision continuously as you learn more.

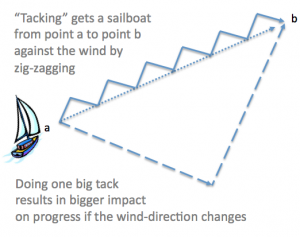

Julian Davies, a developer at one of our clients, likened this to sailing. To travel from point a to point b in sailing you do so in a series of direction changes, called tacking. This is necessary when point b is against the wind.

You could, theoretically, do this in two long legs with one direction change. However, this leaves you vulnerable to changes in wind-direction potentially taking you significantly, perhaps even catastrophically, off course. Tacking is generally done with a series of small diagonal legs where each leg allows you to adapt to the changing wind. These frequent opportunities to read the context, i.e. the wind and currents, means that we will only ever be slightly off course with plenty of opportunity to recover.

Julian likened it to agile development in general but I think it applies equally to what I’m talking about here today.

With big-bang changes, what happens when we’re in the deepest trough of the curve and an opportunity arises? It is much more difficult to change course. With small changes we can put the latest experiment on hold to capitalise on that opportunity. When the wind changes on our projects, say when someone leaves or half the team is ill with a winter flu bug, we can quickly respond to those changes.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Andy Palmer for reviewing this article and providing the snappy title.