If agility to you means maximising the opportunity of realising value early & often while rapidly adapting and responding to market feedback then user stories, applied effectively, can facilitate that. However, one common misunderstanding of user stories seems to hinder teams from achieving the benefits they hope for…

A user story is a “short descriptions of functionality–told from the perspective of a user–that are valuable to either a user of the software or the customer of the software”[1]. You may first encounter stories in this form:

As a microblogger,

I want to find out as soon as others mention me,

So that I can choose to respond while topics are current.

One common misunderstanding of user stories might result in the above example looking more like this…

As a microblogger,

I want a notifications screen showing my mentions,

So that I can find out as soon as others interact with me.

The problem here is thinking of user stories in terms of what the user will have, rather than what they’ll be able to do. This can cause avoidable dependencies that limit your flexibility, reduce your speed to market and limit your ability to change direction based on market feedback.

These dependencies can be dramatically reduced if our user stories steer the conversation towards what the user will be able to do. Let’s explore why…

What the user will have (features)…

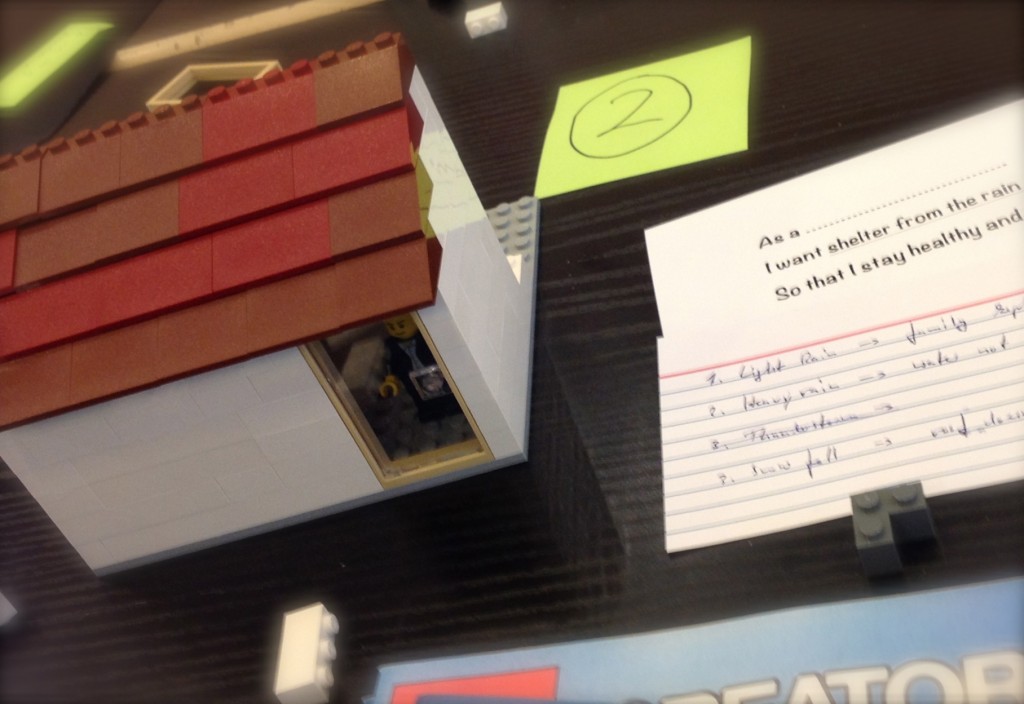

Let’s imagine we envision a house (which will be made of lego in this exercise). What stories would you write for your lego house? Here are some of the typical stories people write:

- As a cook,

I want a kitchen,

so that I can prepare food.

- As a parent,

I want a master bedroom,

so that I can sleep comfortably with my partner.

- As a car-owner,

I want a garage,

so that I can park my car off the street.

Have a think about what’s involved in delivering these stories with a lego house, building our final vision of the kitchen, the bedroom, the garage. If our vision is to have the master bedroom on the top floor, then we can’t have a place to sleep until we’ve built the ground floor. To build our garage ‘iteratively’ we will focus on building the walls first, then put the roof on. Essentially, the architecture drives the order of implementation, not what is of greatest value to us.

The problem here is that these stories are encouraging us to fixate on specific solutions to each problem. Ideally, we want the story to be about what the user will be able to do (i.e. sleep comfortably together), not what they’ll have (a bedroom).

In these examples, as is often the case, the problem we’re trying to solve is there, just in the ‘so that’ part. Getting everyone to share in an understanding of the problem(s) we want solved helps us prioritise based on business value…

What the user will be able to do (capabilities)…

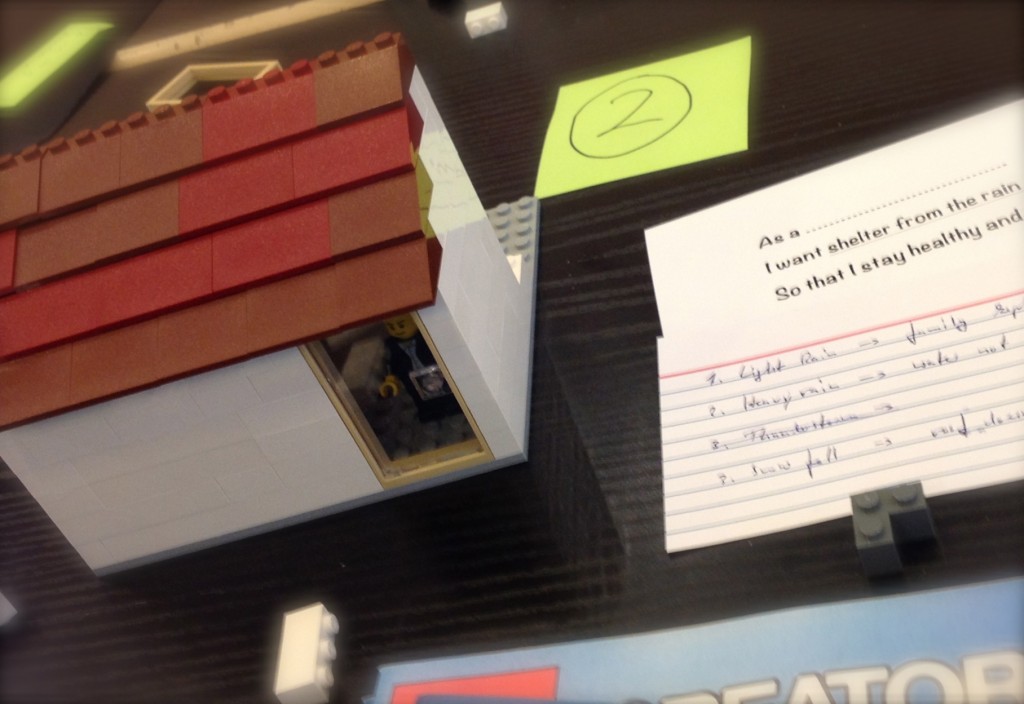

Now, imagine if we had stories like this:

- As a cook,

I want to prepare hot food for the family,

so that we can safely enjoy various fresh foods.

- As a parent,

I want to sleep comfortably with my partner,

so that we can keep each other warm.

- As a car-owner,

I want to park somewhere safe,

so that I can keep my insurance premiums low.

Have a think about the different ways we could initially solve these problems (from camping cookers, a mattress on the floor and a driveway to park the car). We can meet all of these needs rapidly without having to achieve the final vision but make it possible to layer on more and more refinement to each one evolving to the solution and enabling us to discover the solution we really need.

when what we want is “a thing” then what we are describing is not a user story – it is a feature.

Features (“I want a…”) vs. Capabilities (“I want to…”)

Relatively recently, while running my user stories course (with Lego) to delegates at a well known company, one delegate pointed out a difference between the ‘template’ for the two story styles above. They observed that in the case of stories that are really “Features” the format tended to be “I want a…” whereas for stories that were “Capabilities” the format tended to be “I want to…”. Some found ways around this by saying “I want to have a…”.

Interestingly, the original ‘Conextra Template‘ indeed followed “I want to…” and all of Mike Cohn’s examples in his book “User Stories Applied” are indeed capabilities (although sometimes in his explanations he does refer to stories as describing a feature, his examples are generally capabilities).

In short, when what we want is “a thing” then what we are describing is not a user story – it is a feature.

(This short section was added on: 22nd May 2015)

Flexibility & Adaptability…

Each of these stories may be broken down even further. Let’s look at the garage and all the needs a garage might meet

- As a car-owner,

I want to park my car off the street,

so that I can reduce my insurance premiums

- As a car-owner,

I want to shelter my car from the rain,

so that I don’t have to wash it as often.

- As a car-owner,

I want to hide my car from onlookers,

so that opportunists don’t think of stealing or vandalising it.

- As a car-owner,

I want to hinder thieves from driving my car away,

so that I get the lowest insurance premiums.

- As a car-owner,

I want to securely store my tools near the car,

so that it’s easier to do basic maintenance.

- …and so on.

Now think of the different ways we could meet those needs with our lego house?

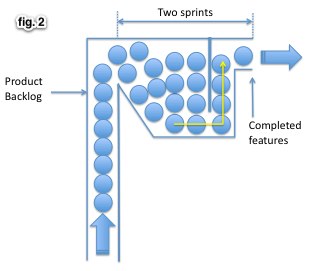

Most of these stories are largely independent of each other and can be delivered in almost any order. This allows us to prioritise the stories based on value rather than the architecture of the final vision.

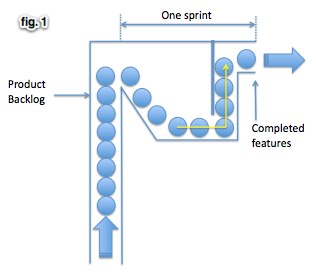

We’ll realise our first piece of value very quickly and continuously gain more and more value until eventually we’ll have a whole garage (if that’s what we really need). If this was something that makes us money, it would mean we’d be generating revenue sooner. Revenue would grow continuously as we continuously grow our product.

It also means we can change direction at any time, for example if we were to start getting feedback taking the garage more in the direction of a workshop with space for a car rather than just a simple garage.

In the real world

I recently helped a client interview people who had from three to five years “experience” with user stories. During the interview I pulled out some index cards and pens. I described a simple product (which was surprisingly similar to early incarnations of Twitter) and invited them to help us write some user stories for our backlog.

What each of them wrote was, essentially, a functional specification, split like use-cases into several cards, except using the above “As a… I want… So that…” template. They explained each story in terms of the screens in the user-journey such as Registration, Login, View Profile, Follow Other Users, Post a Status Update, View Status-Updates and so on. The real issue here isn’t in the name of the story, it’s in what the stories represented in their minds…

I asked them to help us prioritise them based on value. “Registration is most valuable because without it we can’t do anything else”–one interviewee explained. This means that it would not be possible to obtain any feedback about the main value proposition of the product until a number of user stories are complete. Each candidate explained the stories as dependent steps in a journey that, essentially, had to be built in the same sequence as the journey [4].

The main value proposition is sharing updates with people and seeing what others are saying. A simple screen-name (like in a chat room) will do initially. Registration and login are largely about hindering others from pretending to be me. Could there be simpler ways of achieving this at first?

Like I said, I’m not suggesting that any of the story titles that each candidate came up with are invalid, just that they thought of them in terms of the expected solution (what the user will have), not understanding the real problem (what valuable thing the user will be able to do).

In Closing…

With tractable mediums like lego or code (with the right engineering practices around it), we are able to evolve our product to meet each user-need in turn. This is facilitated by thinking of our user stories in terms of the outcome (e.g. shelter from the rain) rather than one possible output (e.g. a roof and four pillars). Ultimately, this way of thinking is one of the key upstream enablers to realising value early & often and brings more opportunity to rapidly adapt to feedback by dramatically reducing dependencies.

——————————-

Experience this for yourself: If you would like me to run this as a hands-on workshop with your team(s), let me know. We’ll explore how user stories work in practice, not only by writing the stories, but understanding the conversation and means of confirmation [3] that complete the practice of user-stories. I can also wrap this in a simulation of Scrum and/or Kanban so that teams can experience how user stories work in practice. I make it accessible to all team members using lego as a metaphor for software, demonstrating the principles described above. We then explore how to apply this to your products, writing some stories or reviewing and refining your existing stories to take what we learn into the real world.

Acknowledgements:

The Lego House exercise that I run has been created by combining my experience with a number of other exercises, including the “XP Lego Game” and Rachel Davies‘ Household Stories exercise.

Footnotes:

[1] “Advantages of User Stories for Requirements” by Mike Cohn (See also his book, “User Stories Applied”)

[2] Typical user story format: http://guide.agilealliance.org/guide/rolefeature.html

[3] There is a lot more to user stories than this three line statement. The simplest explanation is that this is just the ‘Card’ in the three C’s of User Stories: http://guide.agilealliance.org/guide/threecs.html

[4] A key characteristic of user stories is there are few dependencies, if any, between them and each is valuable. This is explained by the mnemonic INVEST: http://guide.agilealliance.org/guide/invest.html